Setting context and expectations: if you don’t play ultimate frisbee, you probably won’t care about this post. Fair warning.

I’m the primary deep deep (abbreviated “deep” for the rest of this post) when my club team plays zone. I briefly played free safety in football in high school, and the positions are similar in a lot of ways. The most personal similarity is that when you do your job correctly, most people don’t notice because throws don’t go up. But when you mess up or something goes wrong, everyone has an opinion about what you did wrong.

I’m writing this to explain how I view and perform the most subjective and criticized decision of the position: when to “call fire” in a zone to signal the transition to person-on-person defense. I’ve had normally-reserved teammates seek me out while walking off the field to say some version of “Why didn’t you call that earlier?” in an openly frustrated tone. For the same reason I write documentation at work, I semi-selfishly want to present this in clear, detailed way so I don’t have to have the same conversation over and over (often with one or both people in an impassioned state).

Overall Efficacy

Based on talking with a lot of people in my frisbee journey, most players seem to think calling fire is relatively simple. Some even break it down to static conditions:

- When the disc breaks the cup past the midline

- When there is a continuation throw after the cup has been broken

- When there has been a successful pass of more than a specific distance (20, 30, 40 yards)

I think the decision should be more nuanced. My view is a zone should be called when the expected efficacy of continuing the zone is significantly less than the transition to person defense. Central to that theory is that transitioning from zone to person has a cost. Everyone who has played the sport can confirm that all but the best drilled teams have at least a few seconds of disorganization after the fire call when defenders are figuring out who’s going to guard who. But people seem to forget about that when talking about fire calls.

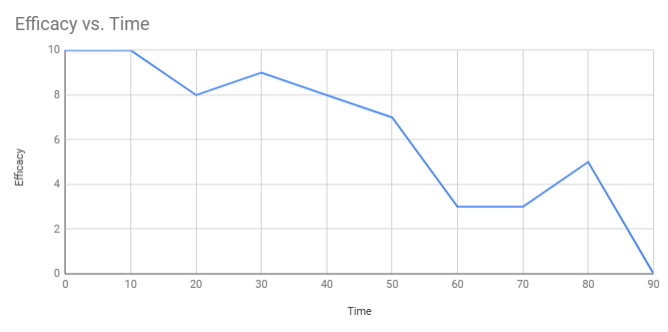

Because I love spreadsheets, here’s a chart that attempts to portray that concept by describing a play from pull to score. I admit it’s overly simplistic, but just roll with it. The point is is 90 seconds in length and follows a pretty standard flow:

- Pull (0s)

- Zone is established (10s)

- Offense slowly works the disc down the field (20-50s)

- Offense gets a big gainer (55s)

- Fire called (60s)

- Defense transitions to person defense (60-70s)

- Person defense (80s)

- Offense scores (90s)

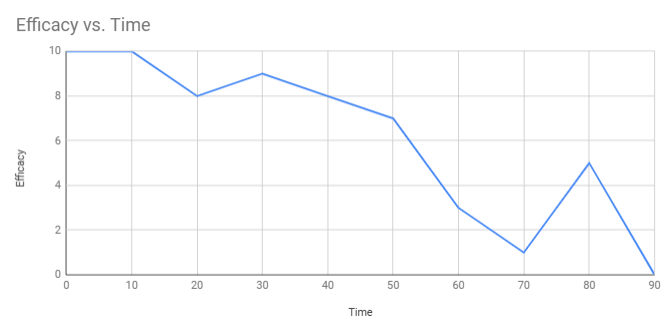

But based on the hundreds of zone points I’ve played at the club level, the chart for that point looks more like this:

The dip at 70s is the crucial difference: in the theoretical chart, the overall efficacy of the defense plateaus between the fire call and the organization of person defense. The second chart shows what I actually see when I call fire: there are several seconds when the overall efficacy of the defense plummets as players figure out who they’re going to guard and try to establish guarding position. Ask any offensive player, and they love those few seconds.

This is crucial because of what I mentioned earlier: a zone should be called when the expected efficacy of continuing the zone is significantly less than the transition to person defense. If one follows that and accepts that the overall efficacy of a defense reliably decreases after a fire call, that means the fire call barrier should be quite high. Reaching that threshold means you think the offensive and defensive player positions:

- Have lowered the overall defensive efficacy to near zero

- Indicate the possibility of the zone regaining even moderate efficacy is very low

Put bluntly, this is frequently the result when I call fire during a point like this:

The offense gets that gainer, I call fire, and in the ensuing confusion, the offense makes one or two throws and ends up with a cutter who is wide open in the end zone. Either nobody picked them up in the post-call disorganization or they used the momentum of their defender (who is trying to establish position) to make a cut that got them significant separation.

Maybe somewhat counterintuitively, if transitioning to person seems unlikely to incur a cost, I probably don’t think it’s appropriate to call fire. If a defense’s state is organized enough state to smoothly transition to person, they are also probably in an organized enough state to continue running the zone. Again, assuming transitioning to person involves a cost, calling it just because the disc moved past midfield or the cup got broken with a single throw does not maximize the defense’s chances for success.

Sometimes things have gone so wrong from the defensive side that nothing is going to help. If the offense somehow throws a long sideline shot and gets a two-on-one in the end zone, it frankly doesn’t matter what I or anyone else on the defense does. But if the the progression is more gradual, that’s when we get into…

Field Spacing/Compression

Zone concepts in other sports I’ve played (basketball, football) are often about funneling players, the ball, or both into areas where defenders are most dense. Whether it’s trapping a player in a “coffin corner” in basketball or using outside leverage to funnel receivers to waiting safeties/linebackers in football, it makes intuitive sense: given a static number of players and a (relatively) static effective sphere around each defensive player, it’s better for the defense if more people are packed into a smaller area. This is supported by the fact that the basic “zone beater” offensive concepts in those sports (and ultimate!) all start with spreading defenders out to create space.

As a result, it confuses me that it’s a nearly universally-held belief in ultimate that when an offense gets the disc into the last third or quarter of the field, the defense absolutely must transition to person.

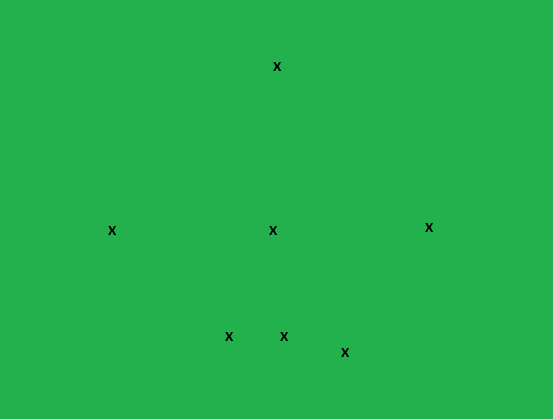

Here’s the basic shape of a 3-3-1 zone defense: 3-person cup, 3-person wall, 1 deep.

Note that the deep is significantly farther downfield than the wall. The first thing most offenses do in this situation is send at least one cutter downfield to stretch the shape, creating space between the deep and the wall. This space can be used for both direct throws and cutter movement/options if the cup gets broken.

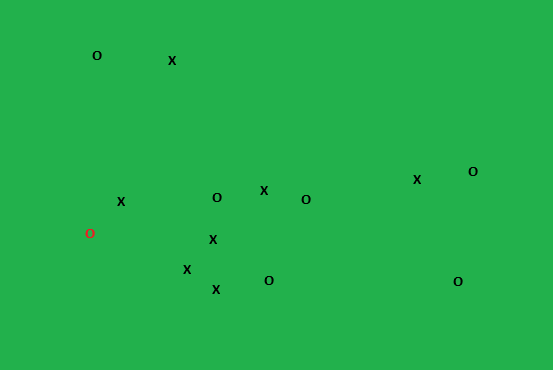

Here’s the same shape near the end zone:

The field is now compressed to just the end zone, so the deep no longer has to worry about long throws and can integrate into the wall. In these situations, I normally read the handler to cover the back corners when the disc is in the center of the field and shade nearer to the end zone when the disc is on one of the sides since I think a sideline throw to the cone is the most common score in goal line offense.

This is a very effective defensive stance at the levels I play. Nobody has to worry about long vertical threats, so they can focus on lateral positioning, and wing recoveries from sideline end zone runs are short/easy. I’ve been a part of many defensive points during which my team has had a lot of success in this situation as long as people actually play it (more on that in the next paragraph). As a result, if an offense slowly works the disc down the field and ends up at the end zone, I will allow the zone shape to compress because I think that is consistently and significantly more effective than calling fire and decreasing our overall efficacy during transition in an area of the field where the end zone is one short throw away.

As we back into that space, many veteran players will get very antsy and all but stop doing their job in the zone because they’re anticipating the fire call. They sometimes even break off into person without me calling fire. This is pretty frustrating on my side. It causes the collapse of an effective defensive shape, and seen from a certain perspective, suggests a lack of trust in my judgement.

Avoiding a transition like this near the end zone is the most common source of friction with my teammates. As I noted, many people who have played the sport at an organized level have been taught that zone defense should transition to person close to the end zone regardless of the events that led to it or the current defensive shape. As best as I can tell, this is because person is considered the default/better overall scheme, so when the defense “gets in trouble” by allowing the offense to advance that far, fire should be called to get to the “stronger” scheme. As shown above, I simply disagree with that; I think zone schemes are actually at their strongest in the compressed end zone space, to the point I have strongly advocated for a tailor-made zone to be my team’s default scheme for a dead disc situation near the end zone.

When talking about this with other players, I’ve found a bit of selective memory happens: when people just continue playing the zone in that situation, we often make the offense swing the disc across the front of the end zone multiple times before we either get a turn or they eventually score. If the team scores, my teammates often seem to forget the good stand we made. Instead, they get frustrated at me for not doing that they’ve been taught is “the right thing.”

That puts me in an awkward position. Saying something as short as “Because I thought staying in zone gave us our best chance at stopping them” can come off a bit dickish. Trying to detail all the concepts I’ve taken hundreds of words to explain in this post before the next pull is both unrealistic and will probably make me seem like I’m being dickish in a different way (being defensive or over-explaining). I’ve always tried to ride the line between the two with varying levels of success. So I wrote this.

Example

I talked generally about when I call fire, but I think it would be helpful to provide a real-world example and different ways to look at it.

The events that led to this:

- The defense is running a 3-3-1

- The hub handler broke the cup and got off a throw to the offensive left wing

- The cup is recovering to the disc, and the defensive right wing is temporarily setting a mark.

- The two poppers are advancing into the space between the wall and the deep

- There is one cutter deep

A large percentage of the people with whom I’ve played would probably call fire here, especially if this was happening past the midline. The cup was broken and is behind the play, there’s a cutter in the deep space, and there’s a lot of room for poppers to work. But I probably wouldn’t call it.

- The disc is on the sideline, effectively cutting off half the field and at least three (maybe four) offensive players as realistic targets.

- One of those targets (trailing hub handler) is not a threat because that pass would kill all forward momentum for the offense and allow the defense to reset their shape.

- The deep cutter is no more of a threat than if the deep were playing person defense and a handler got the disc on the sideline with a loose mark. As long as the deep’s positioning is good (and it should be since there are no other players in the deep space), that’s not an acute threat.

- The mid is chasing the closer popper to cut off the easy gainer to the middle of the field

Most of the time, the defensive right wing sets a flat mark to prevent the deep throw or strike, the disc pauses for 2-3 seconds, the mid successfully blocks the advancing throws, the cup recovers, and the shape get reestablished. This exact play happened during a sanctioned tournament last summer when our other deep was in, and one of my captains likes to tell the story of me running down the sideline screaming “Hold shape! Hold shape!” The deep listened, the cup recovered, and they ended up getting a turnover.

Worth noting: if one more advancing throw is made (most likely to the close popper), I would definitely call it. A strike cut puts them far enough ahead of the cup that recovery is unlikely, and a pass to the center of the field results in a 2-on-1 on the right side of the field for the defensive left wing. As soon as the disc leaves the handler’s hand for either of those throws, I’m calling fire.

A lot of this is dependent on reading the field by knowing where everyone (or almost everyone) on the field is and what the most likely next play will be. That might seem like a lot, but that’s basically the job description of a deep. I don’t have any judgement for people who prefer to keep things simpler, but I think the goal should be to read that information to both cover the field effectively within the scheme and know when to call fire. Just like everyone else, I make mistakes on the field, but I think looking at the fire call through this lens significantly increases my line’s chances of success.

Leave a reply to chrisbell2010 Cancel reply